From Cross Accent Magazine:

the Folk Process Is Alive and Well

Webster defines the term “indigenization” as the practice of “adopting beliefs and customs of others to local ways, “ or “increasing local participation in or ownership of.” Either way, it is a good word to use in defining the practice (the “folk process”) of adapting traditional material of one culture into another culture. One of my favorite quotes on this subject comes from a sixteenth century Moravian bishop:

Our tunes are, in part, the old Gregorian, which Hus used, and, in part, borrowed from foreign nations, especially the Germans. Among these latter tunes are popular airs according to which worldly songs are sung. At this strangers, coming from countries where they have heard them used in this way, sometimes take offense. But our hymnologists have purposely adopted them in order through these popular tunes to draw people to the truth that saves.1

Another Moravian, Clifford Edwin Bair, in an article written for The Hymn, journal of the Hymn Society in the U. S. and Canada, writes:

| Jesus was the first god who had become truly human . . . This fact required a new, more intimate expression, and the Spiritual Songs became just that. They were most likely love songs to Jesus, very personal prayers, and ballads about his remarkable life here on earth. They could very well have been “indigenized” from popular culture in contrast to the hymns and psalms which came from the worship life of the Greeks and Hebrews. |

The sources of the tunes were Gregorian chants, secular folk songs, and tunes with Latin verses used for personal devotions. . . And then there were tunes “composed,” that is, “put together” by Luther, Walther [we could add Klug, Werckmeister, Freylinghausen, Rhau, König, Schumann, Marot] and other early church fathers and musicians. The secular folk tunes always had dance rhythms, often in triple meter, which were retained in the Scandinavian countries.2

Here we see ample evidence of free adaptation. The German hymnologists tended to change the tunes from dance rhythms to a more sober 4/4, or to “compose” them into syncopated rhythms which often varied the meter from one measure to the nest. This became the characteristic which we define as “chorale.” The tendency of Scandinavian editors to “indigenize” or re-adapt the tunes to dance rhythms was clearly upsetting to the Germans – it still is. But then, the Catholics were furious with the Reformers for what they did to the chants, and the Germans were upset with the Swedes for what they did to the chorale, the Swedes are upset with the Liberians for what they did with the Swedish folk hymns, the Liberians were upset with me for what I’ve been doing with the African songs, and I’m upset with the American churches for singing them as if they were Gregorian chants. So, we’ve come full circle!

Rather than all this “upsetness,” wouldn’t it be more productive to accept the fact that borrowing ideas from another culture is a natural phenomenon? After all, this process has been going on since the origins of human life and will no doubt continue until the end of it. The compliers, editors, adapters, arrangers, whatever, that are responsible for all this are not necessarily less brilliant or creative than those who specialize in original composition. I like to think of it as a recreative activity, or the art of recycling. For the liner notes on an album by Kirsten Braaten Berg, a Norwegian musicologist wrote this:

Traditional music, like the god Janus, has two faces. One of them is turned backwards, its gaze directed at what once was. Traditional music’s other face is turned forwards, surveying the present, absorbing its teeming life, and this ear can hear other notes and sounds, unknown and constantly changing, and something of this can be fused into the soul of the music without renouncing its own. This is a paradox: tradition without renewal is stagnation. But not just innovation for the sake of it. It all depends on who does it.3

We’re all familiar with the most well-known examples: “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded” (a 3/4 sensuous love song changed to a 4/4 chorale) and “Wondrous Love” (a bawdy sea chanty turned into a powerful Lenten hymn), but approximately 250 hymn tunes in the Lutheran Book of Worship have come to us as a result of this indigenization process. To deny the process is to deny some of the very best hymns of the church.

Anscar Chapungco, the oft-quoted Filipino liturgiologist, is writing here about liturgy, but the same thought could be applied to hymnody:

The liturgy is inserted into the culture, history and tradition of the people among whom the church dwells. It begins to think, speak and ritualize according to the local cultural pattern. If we settle for anything less than this, the liturgy of the local church will remain at the periphery of our people’s cultural experience.4

| Rather than all this “upsetness,” wouldn’t it be more productive to accept the fact that borrowing ideas from another culture is a natural phenomenon? After all, this process has been going on since the origins of human life and will no doubt continue until the end of it. |

In this article I will present examples of a continuation of this tradition for the purpose of demonstrating that the process is alive and well in our time. Most of the examples represent the Scandinavian practice of returning tunes to their traditional origins. The Danish compliers especially loved to adapt German tunes, such as Vater unser, Erhalt uns Herr, Christ ist erstanden, and set them to the more incarnational texts of Kingo and Brorson. We could think of the “Spiritual Song” tradition as incarnational in the sense that Jesus was a unique god. There have been humans who have made themselves gods (Nero, Caligula, Hitler, etc.), but Jesus was the first god who had become truly human, who had a mom and dad, siblings, and good friends with whom he walked, talked, and ate. This fact required a new, more intimate expression, and the Spritual Songs became just that. They were most likely love songs to Jesus, very personal prayers, and ballads about his remarkable life here on earth. They could very well have been “indigenized” from popular culture in contrast to the hymns and psalms which came from the worship life of the Greeks and Hebrews. The fact that Paul lists them (Ephesians 5:19 and Colossians 3:16) right along with the psalms and hymns, and doesn’t scorn them, indicates that they were an important part of the spiritual expression of the early Christians. The importance of this subject has been elevated in our time because of the revolution in mass communications, giving people access to and appreciation of musical styles they would previously not have known.

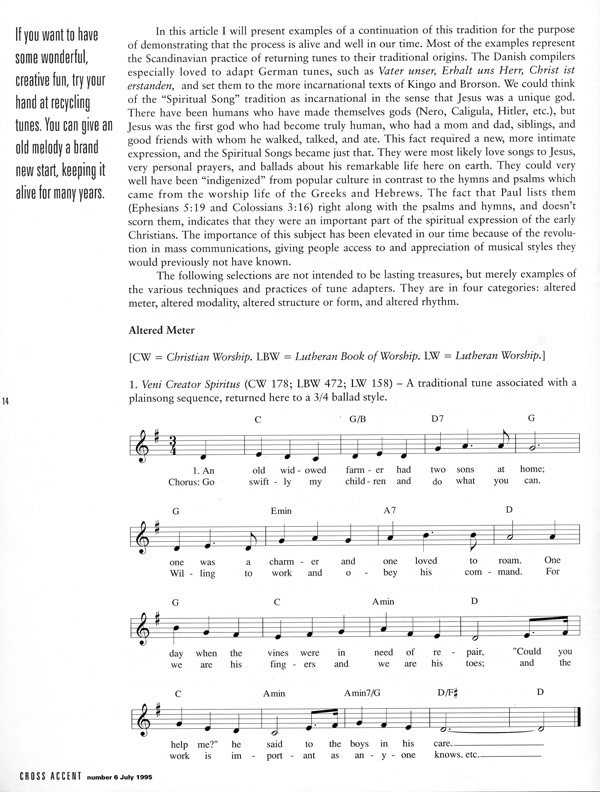

The following selections are not intended to be lasting treasures, but merely examples of the various techniques and practices of tune adapters. They are in four categories: altered meter, altered modality, altered structure or form, and altered rhythm.

Altered Meter

[CW = Christian Worship. LBW = Lutheran Book of Worship. LW = Lutheran Worship.]

1. Veni Creator Spiritus (CW 178; LBW 472; LW 158) – A traditional tune associated with a plainsong sequence, returned here to a 3/4 ballad style.

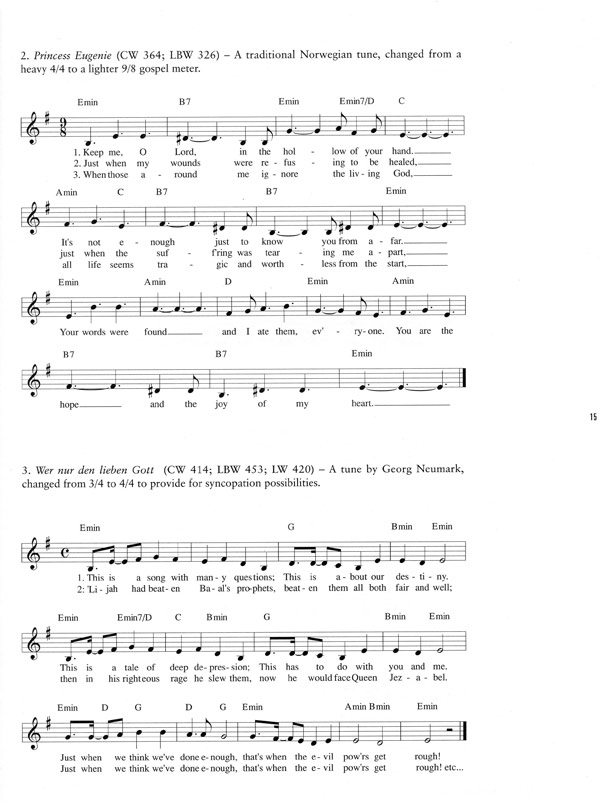

2. Princess Eugenie (CW 364; LBW 326) – A traditional Norwegian tune, changed from a heavy 4/4 to a lighter 9/8 gospel meter.

3. Wer nur den lieben Gott (CW 414; LBW 453; LW 420) – A tune by Georg Neumark, changed from 3/4 to 4/4 to provide for syncopation possibilities.

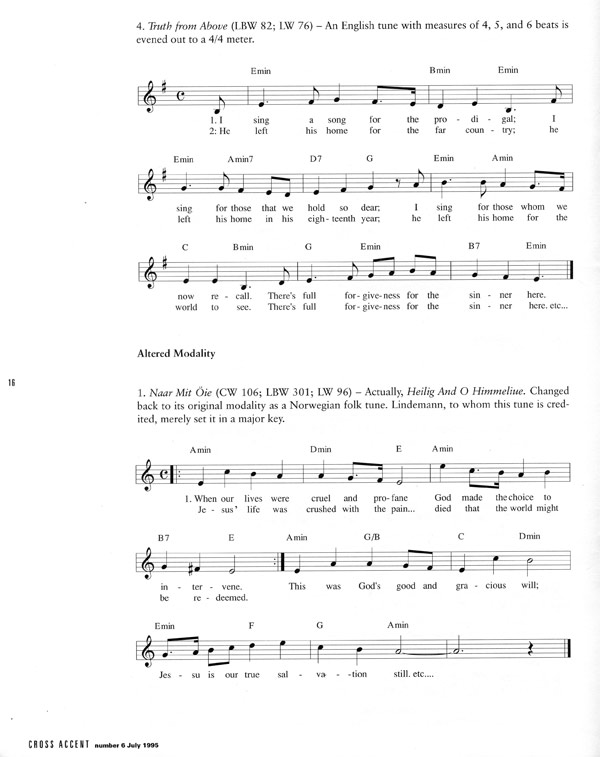

4. Truth from Above (LBW 82; LW 76) – An English tune with measures of 4, 5, and 6 beats is evened out to a 4/4 meter.

Altered Modality

1. Naar Mit Öie (CW 106; LBW 301; LW 96) – Actually, Heilig And O Himmeliue. Changed back to its original modality as a Norwegian folk tune, Lindemann, to whom this tune is credited, merely set it in a major key.

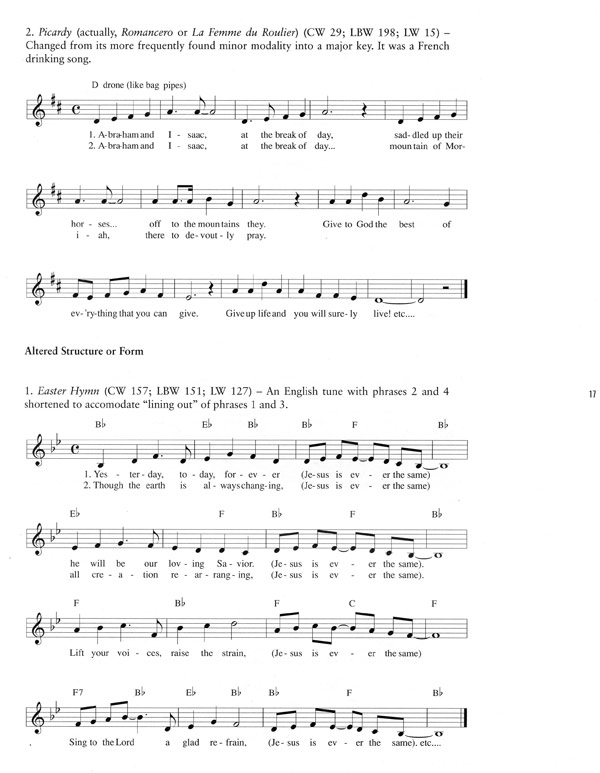

2. Picardy (actually, Romancero or La Femme du Roulier) (CW 29; LBW 198; LW 15) – Changed from its more frequently found minor modality into a major key. It was a French drinking song.

Altered Structure or Form

1. Easter Hymn (CW 157; LBW 151; LW 127) – An English tune with phrases 2 and 4 shortened to accommodate “lining out” of phrases 1 and 3.

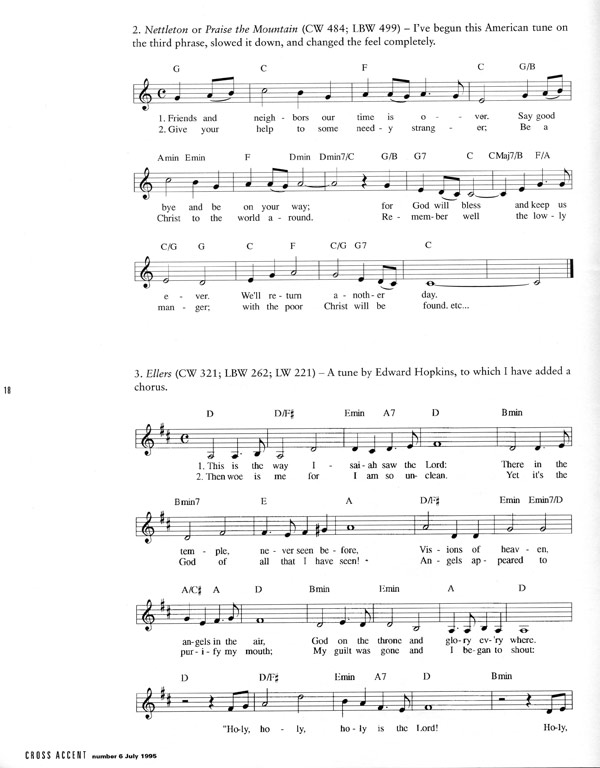

2. Nettleton or Praise the Mountain (CW 484; LBW 499) – I’ve begun this American tune on the third phrase, slowed it down, and changed the feel completely.

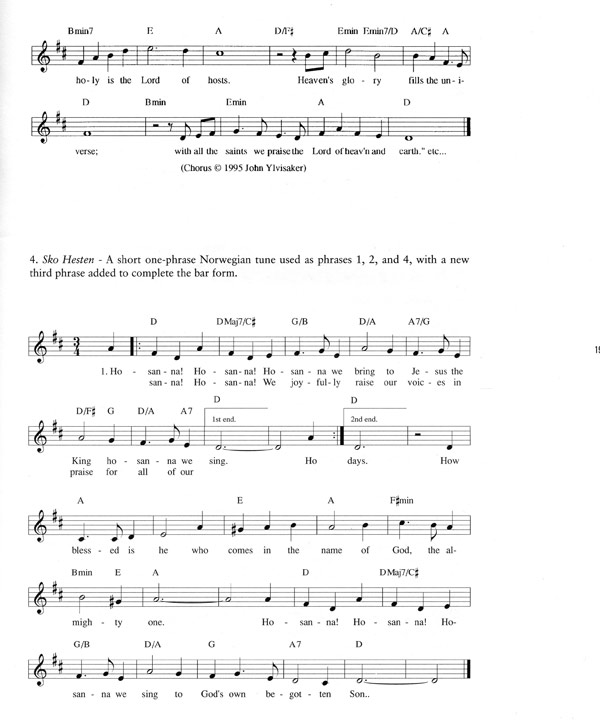

3. Ellers (CW 321; LBW 262; LW 221) – A tune by Edward Hopkins, to which I have added a chorus.

4. Sko Hesten – A short one-phrase Norwegian tune used as phrases 1, 2, and 4, with a new third phrase added to complete the bar form.

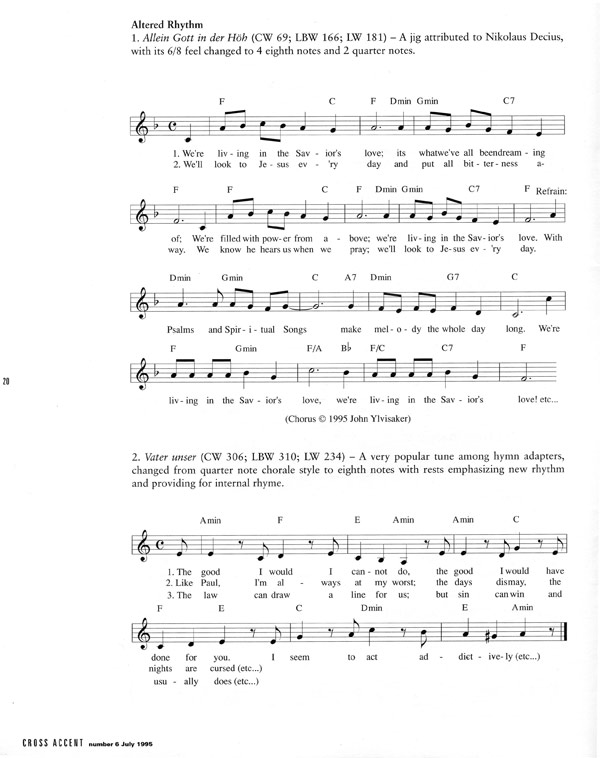

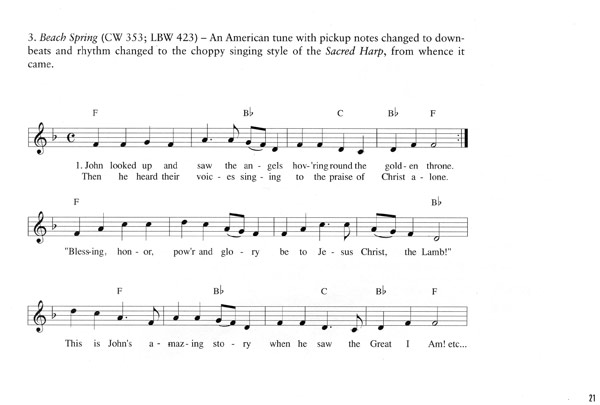

Altered Rhythm

1. Allein Gott in der Höh (CW 69; LBW 166: LW 181) – A jig attributed to Nikolaus Decius, with its 6/8 feel changed to 4 eighth notes and 2 quarter notes.

2. Vater unser (CW 306; LBW 310; LW 234) – A very popular tune among hymn adapters, changed from quarter note chorale style to eighth notes with rests emphasizing new rhythm and providing for internal rhyme.

3. Beach Spring (CW 353; LBW 423) – An American tune with pickup notes changed to downbeats and rhythm changed to the choppy singing style of the Sacred Harp, from whence it came.

The tunes acquire new texts because of the change in mood and rhythm caused by the alterations. In this case I was trying to return them to their song origins, so the texts are simpler lyrics, reminiscent of biblical songs and carols of the medieval period. In a footnote to an article in The Hymn on James O’Kelly’s collection, Hymns and Spiritual Songs, the author writes:

The “songs” are in a separate section from the hymns at the end of the book . . . The “songs” tend to be cruder than the hymns and include short choruses, refrains and repetitions that are reminiscent of folk songs.5

Song writing is quite different from hymn text writing. The texts of songs are called lyrics, not poems, and they include much more repetition with refrains, choruses, call and response techniques, and space for “lining out” the words before the people sing them. The sound of the rhyme scheme is more important than the look; so, rather than using “eye” rhymes (“love” with “prove,” “one” with “alone”), the song writer will be more concerned with the sound of the rhyme, even though the ending consonants are not the same. There is also more attention paid to rhyme as an aid to memory, with lots of internal rhyme schemes utilized. The texts are more subjective and less metaphorical.

The indigenization process is something that has been going on for countless centuries, but in the twentieth century we have become much more self-conscious about it. We’ve even started putting copyrights on harmonizations and simple arrangements (David Evans, Winfred Douglas, Ralph Vaughan Williams) which a good player can whip out in a few minutes. Adaptations and harmonizations should never be locked up in someone’s private copyright. Sooner or later we run out of successful alterations or pleasing harmonies, and natural process is thwarted. If the tune is in public domain, it should remain available in order that this process may continue.

So, if you want to have some wonderful, creative fun, try your hand at recycling tunes. You can give an old melody a brand new start, keeping it alive for many years. These songs are also fun to use with children’s choirs, informal worship settings, and hymn-sings. Keep in mind that the melodies are timeless and indestructible. They don’t belong to the Germans or to the Scandinavians or to me, they belong to everyone. It is my hope that church musicians will recognize the legitimacy of this process, in order “through these popular tunes to draw people to the truth that saves,” as the Moravian bishop put it.

Indigenization: the art of “adopting beliefs and customs of others to local ways.” The folk process should be alive and well in the twenty-first century.

1 Edmund De Schweinitz, The History of the Church Known as the Unitas Fratrum or the Unity of the Brethren, second edition (Bethlehe, PA: Moravian Publication Concern, 1901), pp. 402-03.

2 Clifford Edwin Bair and Alma W. Bair, “The Restoration of the Traditional Interpretation of the German Chorale.” The Hymn, XLV/3 July 1994, p.36.

3 Paul-Helge Haugen, liner notes to the album Min Kverdarlund, Kristin Braaten Berg (Heilo HCD7087, Oslo, Norway, 1993).

4 Anscar J. Chupungco, Liturgical Acculturation: Sacramentals, Religiosity and Cathechesis (Collegeville, MN: Order of St. Benedict, 1992), p. 30

5 J. Timothy Allen, “James O’Kelly’s Hymns and Spiritual Songs.” The Hymn, XLIII/4 Oct. 1992, p. 28.

John Ylvisaker, well-known writer and performer of spiritual songs, publishes music under the imprint of New Generation Publishers, Waverly, Iowa.